- Home

- Kat Hausler

Retrograde

Retrograde Read online

Praise for Retrograde

“[E]ach word that is spoken or left unsaid becomes important in a cat-and-mouse mind game that gives this pensive story some elements of a thriller. The love that’s described is always on thin ice (‘But the moment he touches her, the spell will break, and they’ll just be two people in bed together, without any enchantments’). Hausler’s ability to describe the precarious state of the emotions involved is consistently convincing…. A strongly written tale about resurrecting a marriage under the most unusual and mysterious of circumstances.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“This disturbing, haunting and powerful story explores the minutiae of the relationship between the couple as they start to live together again… [T]he ending was a masterpiece of the power of ‘less is more’ in storytelling—but if you want to know what it is, then you will have to read this wonderful novel.”

—Linda Hepworth, Nudge Books

“Hausler’s debut novel was an incredibly beautiful look at love put through the test of time. Retrograde is very much about the nature of love as it features many of the ups and downs of a difficult relationship. From touching dates and admiration to petty fights and full blown arguments, Hausler’s breakout has it all.”

—Melissa Ratcliff, Paperback Paris

RETROGRADE

A NOVEL

KAT HAUSLER

RETROGRADE

Copyright © 2017 by Kat Hausler

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used, reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For information, contact Meerkat Press at [email protected].

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

ISBN-13 - 978-1-946154-02-6 (Paperback)

ISBN-13 - 978-1-946154-03-3 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017911522

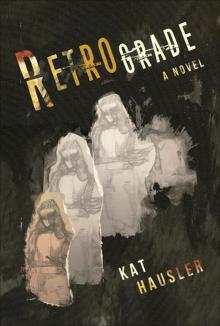

Cover art front cover, “The Disappearing,” and back cover, “Love,”

© 2017 by Laurel Hausler

Book design by Tricia Reeks

Cover design by Tricia Reeks

Printed in the United States of America

Published in the United States of America by Meerkat Press, LLC, Atlanta, Georgia www.meerkatpress.com

Contents

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

Helena

Joachim

About the Author

“That awful thing, a woman’s memory!”

—Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

JOACHIM

Leila left Joachim when she found out he was married. It wasn’t the only reason, but it was a reason. There’s always enough resentment between two people for a separation; all it takes is a catalyst. That’s what Joachim tells himself, anyway.

In this case, he’d made an innocent remark about his wife. He can’t remember afterward what he and Leila were talking about, what caused him to say: “My ex-wife always used to say that.”

He must’ve said it a million times. But this time, the million-and-first time, Leila had a rare moment of curiosity about his past and asked, “How long ago did you actually get divorced?”

“Well,” he said, “the thing is.”

The thing is that they aren’t divorced. Not because there’s any lingering chance of reconciliation, but for the simple reason that Joachim can’t reach his wife. For almost three years, he hasn’t had any idea where she is. Not only did she change her number after she moved out, but all of his emails were either returned automatically or never answered, whether he sent them to her, her parents, or the friends—and that had been most of them—who sided with her. No one he called would admit to knowing where she was, and that got embarrassing fast. Her parents had his number blocked, and at the time, he was too ashamed to call from another phone. What would he have said?

After all, he doesn’t really want to talk to Helena. He just feels that he should be able to if he needs to. To divorce her, for example.

It’s not that he’s in any hurry to get married again; he’s just tired of being married to someone he never sees. It’s like one of his arms up and pulled itself free of him, and is out there now, shaking hands and signing documents in his name. He doesn’t like knowing there’s a part of him out there without him.

But Leila wasn’t convinced. She said it was just like him not to have said anything and that he was always keeping important things from her.

“Yeah, that’s what my ex-wife—” he started to say, out of habit.

Leila piled her dark, bouncing curls into a bun on top of her head, always a sign that she was about to leave. He reached up to stroke her hair and she slapped him hard enough to leave a mark.

“For heaven’s sake, darling, I haven’t heard from her in years. I could probably have her declared legally dead.”

“I’m leaving,” she said.

He managed to keep himself from repeating his fatal remark a third time. Unlike his wife, the first time Leila said she was leaving, she actually did.

• • •

He’s surprised at how abrupt the break is. Leila comes once to pick up her things and leave his spare key in the mailbox. She had astonishingly little at his place, for a relationship of almost a year. He cleans the apartment twice after she leaves but finds nothing more than a few stray hairs on the bathroom floor. And no teary phone calls, no one ringing his doorbell at 3:00 a.m. to say “I didn’t mean it.” He calls her after two weeks, and she says she’d appreciate if he didn’t call anymore. So he doesn’t.

• • •

Leila wasn’t the first woman in Joachim’s life post-marriage, just the first to stick around this long. Careful experimentation after Helena packed her things and slipped below the radar has shown that “my ex-wife” meets with more favorable reactions than phrases like “my estranged spouse” or “married but separated.” He doesn’t consider it lying, because it’s true that they’re no longer husband and wife. But it would be a lie to refer to her simply as “my ex,” and try to play down the most important event in his twenty-some years of romantic experience.

He doesn’t miss Helena and he isn’t still in love with her. In fact, he rarely thinks of her, except to identify a certain period of his life—When I was married—or when something specific reminds him of her.

He doesn’t think of her after his breakup, except as the cause of it. Just after the door closed behind Leil

a, there was an instant in which his mind leapt toward the memory of his separation from Helena, but fell short of it. He didn’t want to remember. It wasn’t a clean break like this one, but a state of almost unbearable misery that lasted for months.

The week after Leila told Joachim not to call, he has a big assignment that takes up most of his attention. A major client complained that the campaign he designed for their new line of granola bars wasn’t catchy enough. The result is that he has to redo a month’s work in four days, and do it better than the first time around.

Although he clocks about twelve hours of overtime and is exhausted by the time he turns in the new proposal Friday evening, he can’t bring himself to go straight home.

Instead of hurrying to the U-Bahn station as usual, he strolls toward the Landwehr Canal. Once he’s crossed the bridge over it, he stops abruptly, no longer knowing what to do. A bicyclist swerves to avoid him, rings his bell, and curses. Joachim responds with an embarrassed smile. He follows the trail along the bank of the canal and sits down on the first unoccupied bench. He feels like he’s waiting for something, or someone. A pair of joggers gallops by, leaving behind snatches of conversation about the Eurozone Crisis.

Although the water is just a few meters away, he can’t see it from where he’s sitting because of the thick undergrowth and tufts of yellow weeds. It’s late July, but doesn’t feel like it; all in all, it’s been a disappointingly cool summer.

He sits a while beside the invisible water, thinking empty thoughts about the weather. He’s aware that he and Leila walked along this canal together the month before, that Helena was living in this part of Kreuzberg when they first met, but it’s no use thinking about these things, trying to find a meaning that isn’t there. Just a couple more memories to clutter up the back of his mind with all the other irrelevant debris that’s accumulated over the years: choruses of songs he listened to in his youth, illustrations from Shockheaded Peter that gave him nightmares as a boy, the dates of the Thirty Years’ War.

He begins to feel weak. I must be hungry, he tells himself. And tired. Have to make an early night of it. But he doesn’t move until the first stars have appeared at the edge of the sky. Someone—who was it? Helena, trying to make up for his thoroughly unmagical childhood?—told him you could make a wish on the first star you saw each night. But he can’t remember which he saw first, or decide what to wish for.

Walking to the station, he decides it must’ve been Helena who told him that, but he can’t be quite sure and that bothers him, though neither the silly superstition, nor the memory of being told about it, ever held any significance for him. I’m getting old, he thinks.

• • •

The feeling of weariness remains when he wakes the next morning, and everything seems to take longer than usual. Shaving in front of the bathroom mirror, he counts a few more gray hairs on his chin. The pouches under his puffy brown eyes are like two deflated balloons, and he feels nervous combing the thin, ash blond hair at his temples, as if he might startle his skittish hairline into retreating further uphill.

HELENA

Exactly 3.24 kilometers away, Helena is looking into her bathroom mirror, weighing pros against cons. Her cheeks, so flushed with anxiety she doesn’t need blush, make her gray-blue eyes shine despite the faint circles below them. She’s painting on a glistening layer of lip gloss and wondering whether blue eye shadow is too much for a first date.

It’s not, she decides, and smooths moisturizer onto her eyelids to keep the powder from collecting in the fine lines running through her skin. On the whole, she thinks she looks pretty good, though her wavy, copper-colored hair was so uncooperative she had to confine it to a tight knot at the back of her head.

No, the eye shadow is too much for so early in the day, and it draws attention to the shadows under her eyes. Tobias has already seen a picture of her, but she wants him to say she’s prettier in person.

She washes off the eye shadow and puts on too much perfume, telling herself it will wear off before her date. She doesn’t want to seem like she’s trying too hard.

She leaves the bathroom and, not knowing what else to do, begins to clean her already clean studio apartment. She wants to laugh at her absurd anxiety, but she’s too anxious even for that. How long has it been since she kissed a man, or even went on a date?

Much too long. At thirty-three, she hardly has the time to spare. She washes the few dishes in the sink, washes her hands and rubs lotion into them. It isn’t that she avoided dating after her separation from Joachim; it just didn’t happen.

There was even a time, a few months after, when she began answering personals ads. Her friends said it would help her move on. She would’ve preferred to meet men in some more conventional way, say at a bar or party, but no one approached her. There must’ve been—maybe there still is—some subtle signal in her body language telling them to keep away. Which, on a certain level, was what she wanted.

Back then, about three years ago now, she went home and sobbed after each date. Home was with her best friend Magdalena, and once she’d cried herself out, the two of them would take a walk around the block. Helena felt like an invalid who couldn’t be let out on her own.

She sits down on the sofa and sighs. She’s doing it again: hoping too much. It’ll make it that much harder when nothing comes of it. But then that attitude is just as bad—she shouldn’t give up on Tobias before she’s even met him.

Tobias is the divorced cousin of one of Helena’s coworker’s husband’s friends, putting enough distance between them for it not to be awkward if things don’t work out. None of Helena’s coworkers at this agency know she was married—or that she still is. It isn’t relevant. At the same time, many were surprised to learn that she was single.

“But you’re so pretty!” Doro, who sits next to Helena, burst out when the subject first came up in the office kitchen. Doro is in her forties with Helena-can-never-remember-how-many children and a pleasant husband who stays home to tend to them. Children are a subject Helena avoids bringing up, because discussing them somehow always gives her a sudden, suffocating pain in her throat, like swallowing something large and sharp.

Like all happily married women with inexplicably single friends, Doro searched all seven degrees of her acquaintances until she came up with a possible match. Helena demurred, but only briefly. She trusts Doro’s judgment. She has older and better friends, but sometimes it’s hard to be around them. They always want to talk about the past, and even if they don’t, it’s there, the elephant in every room. Sometimes she feels ungrateful for seeing so little of them, all those mutual friends she won in a kind of custody battle after leaving Joachim. She’s known Magdalena since they were girls, but that time is overshadowed by more recent memories. She met Sepp, Susi, and Susi’s husband, Thomas, through her old job, and they were always her and Joachim’s friends, even if they took her side in the end. Maybe it’s natural; maybe they just belong to another part of her life. Anyway, why think about that now, when everything’s so strange and exciting? She’s so used to feeling alien to the world of romance that the mere thought of becoming involved with someone has an exotic, thrilling appeal.

When she can’t stand waiting around anymore, she goes up a floor to see whether Julie is home. Julie’s a sloppy, lovable, and fearless strawberry blonde from England who befriended Helena by force one day when she came to pick up a package Helena had signed for. Julie will know the right way to look, the right things to say.

But Julie doesn’t answer, even when Helena rings her doorbell a second time. Was this the week she was going to visit her parents? Julie’s the kind of person who barely knows her own vacation plans until she gets on a plane, and Helena can’t remember. She can’t bring herself to go back into her apartment, but the thought of telling Julie about the date later on reassures her. Or Doro, if Julie’s out of town, though she can’t say anything too harsh about someone Doro knows, so maybe Magdalena or Susi, if she can get herself to call

them. It’s hard to keep up with old friends, harder still when they’re part of a time you don’t want to remember.

JOACHIM

The selection at the bakery is disappointing—after all, it’s quite late for breakfast—but Joachim is too embarrassed to leave again after he walks in, so he buys a stale-looking Berliner pastry, a cup of coffee, and a copy of the Tagespiegel to read while he eats.

Because it’s a warm day and the bakery sells ice cream, a procession of parents and small children files in and out, bickering and cajoling and dripping on the floor, some taking seats to raise the ambient noise a few decibels.

Usually, Joachim overlooks children the way a wild animal overlooks street signs: they have no meaning for him. But in the strange mood that he’s in, they catch his attention, and an even heavier weariness settles over him despite his long sleep.

He feels old. Not in comparison to the children, but to their parents, perky young couples who still hold hands. Having children, he realizes, is something he didn’t do. Never before has it been so clear to him that the part of his life in which he might have done so is over.

How ridiculous, he thinks. I never wanted children that badly. He forces down his doughnut—soggy on the inside where the jelly soaked in, and dry on the outside, with enough powdered sugar to choke on—and washes it down with coffee. When he wipes his mouth, it feels raw, as if the doughnut had been powdered with sand.

There’s nothing to get so sentimental about. He must’ve slept poorly. Opening the newspaper between himself and the laughing, crying, slurping, chattering families, he struggles to focus on the articles in front of him: “Completion of Airport Postponed Again,” “CDU Politician Accused of Bribery,” “UN to Send More Troops.”

But why has it been so long since he had thoughts like these? Maybe he hasn’t allowed himself to. Helena wasn’t able to have children, and although they sometimes mentioned adopting, it was always something they might do down the road, when they were ready. Which they never were, because there was always some other difficulty, something to fight over, an impossible issue that had to be worked out. When the time came that Joachim could’ve had a child, becoming a father was the furthest thing from his mind.

Retrograde

Retrograde