- Home

- Kat Hausler

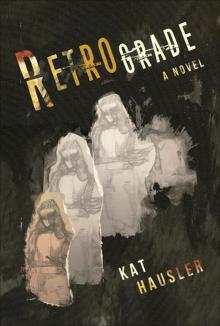

Retrograde Page 2

Retrograde Read online

Page 2

For the first time, he allows himself to look back on what must’ve been the ugliest period of his life.

It was the year a local paper ran the headline: “Cheating: Berlin’s National Pastime.” Helena was particularly jealous and irrational, though he’d never given her a reason to be. In their calm moments, they both knew this had more to do with her insecurity and the many other problems in their marriage than any actual suspicions, but their relationship was swept from storm to storm, and calms were few and far between. Her office was laying off staff, and he wasn’t getting enough freelance work to support both of them. There were nights he couldn’t sleep for worrying. Not about any one thing in particular, but about how things could possibly go on the way they were. Outside of his home, he felt ashamed and dishonest, because he played the good husband when, again and again, his evenings ended with Helena crying until she wretched in the bathroom sink, and him on the living room sofa, sniffling, terrified, but never crying loud enough for her to hear. It seemed to him that these were strange, inexplicable problems no one else had, peculiar blights that reflected on his character. Things he somehow deserved. His parents had certainly thought so when he alluded to the situation, but they were the wrong people to confide in. Even if he’d found the right person, he wouldn’t have known what to say.

Staring blindly at his Saturday morning—or now after-noon—paper, he remembers what a relief it was when they finally decided to take some time off. “A break,” they called it, as if their exhaustion were merely physical, and they could carry on as soon as they’d stopped to catch their breath.

Helena’s childhood friend Magdalena offered up her spare room, and he stayed behind in the apartment. It was remarkable how civil they were, once the decision was made. Maybe because they were up against something larger than themselves, a darkness against which all their petty squabbles paled to a muted, funereal respect. He helped her carry her bags to the cab waiting downstairs and kissed her on the cheek. They hadn’t set a definite time frame, but she said she’d let him know when she was ready.

He didn’t call for the first few days; then he called every day. She rarely picked up. Sometimes she’d send a message saying she was busy, but not with what or whom; other times he went without any answer at all.

Still, he didn’t feel the gutting sorrow he knew he would if their separation were permanent. Helena wasn’t gone from his life; she was merely absent, as if out of town. Once she’d been called away unexpectedly to help with a photo spread and been similarly unavailable, albeit only for five days. There was nothing to do but keep busy, so he did it, avoiding their mutual friends and spending more time on assignments, job applications, and drinking with colleagues from his part-time corporate design gig. He was always among the last to leave the office or the bar. The apartment was so quiet in those first days.

He stopped calling Helena, and she began to call him once every week or two, never for more than a few minutes at a time. She sounded happy and very far away. After she hung up he held onto the phone a moment too long, lonely as an exile to the ends of the earth. But they didn’t fight on the phone.

On one particularly grim Saturday in November, he dragged himself to a coworker’s going-away party. He wasn’t close to the man but felt the need to be among people, away from the stillness that burned in his ears, and all the surfaces in his home that were cold to the touch.

The party was a drag and broke up early; his coworker had movers coming in the morning. But some of the guests moved on to another bar and then another, and after all, no one was waiting up for Joachim.

Vague and dizzy at the third bar, he found himself talking to a girl with dark hair and bare legs that glistened like silk stockings under her short skirt. He felt so virtuous letting her know he was married, in that way that always sounds so forced: “Ah, Provence? My wife and I always…” And he never took off his wedding ring.

There was nothing special about the girl, and that made him feel safe. She was short, curvy without being fat, with a bland, pleasant face. Red lipstick. He felt the blood flowing below his waist when he looked at her, but when he left the dance floor to get her a drink, he immediately forgot what she looked like. Besides, she knew he had a wife. Even if he was taking time off and free to do as he pleased, he knew and she knew that he had a wife.

Still, her attention was pleasant, therapeutic after months of fighting with Helena, and weeks of being ignored by her. When they’d agreed to take a break, he’d had no intention of seeing anyone else. Wherever their marriage might be headed, he had his hands full with Helena. Getting involved with someone else would’ve been like taking a break from a marathon to swim a few dozen kilometers.

But it was easier than he’d thought. He didn’t decide to go home with Ester based on the current status of his marriage; rather, upon finding himself in a loft bed in her filthy apartment, he recalled this “time off” with relief, clutching it like an amulet to ward off guilt.

The sex was mediocre. They were both drunk and Helena was better in bed. But since this sex didn’t come at the price of recriminations, tears, and fights over the pettiest issues, since there was no pathos and no panicked, urgent need to solve all the problems in their two-person universe before he fell asleep, he saw Ester a few more times in the next couple months. He made his situation as clear as he could: despite the bleak outlook of his marriage, it was still his top priority.

Ester didn’t seem to mind, maybe because she didn’t believe him. He noticed this and felt somehow at fault for not convincing her. But he reminded himself that he’d told her nothing but the truth from day one.

A few weeks into the new year, Helena called and said she missed him but she needed a little more time. She asked how he was, and they talked a while without saying anything. Another month passed and she said she was ready if he was.

It had been a couple weeks since he’d slept with Ester, and he hadn’t heard from her in the meantime. Although he knew it was cowardly, he called her to break it off. He told himself he didn’t trust himself to see her, but really he just wanted to avoid an inevitably unpleasant situation.

She didn’t sound too upset, and he was relieved, though on some level also offended. She must have many other Joachims lined up, he thought. After all, they’d only seen each other a handful of times. He was happy to have the whole thing behind him.

Helena returned looking cheerful and well-rested. She came in, dropped the handle of her suitcase, and wrapped her arms around him for a good five minutes without speaking. He felt so secure in her warmth he could’ve wept like a child.

“Hey,” she said. “I think we’re gonna be okay.”

But they weren’t.

Three weeks after Helena’s return, Ester called. She needed to see him, she said. It was urgent. He refused. He hadn’t told Helena about the affair because it had taken place outside of time, because it was irrelevant. He wouldn’t see Ester again.

To his surprise, she insisted. Gone was the flippant girl who didn’t mind about his wife. When he told her it was absolutely impossible, she hung up but turned up at his door that evening. He didn’t know where she’d gotten his address, since they’d always been at her place. She must’ve looked through his wallet at some point. Miraculously, Helena wasn’t home from work.

He took Ester by the arm and led her downstairs, away from his home. It was drizzling and chilly, but he didn’t stop to zip his coat. He took her into a dingy old men’s bar around the corner, where the air smelled like stale smoke, stale beer, and staler flesh. He wanted to push her in and leave her there, as if removing her from his life could be that simple. Afterward, maybe even at the time, it seemed to him that he already knew what she was going to say.

“Joachim, we’re having a baby.”

And of course it was right to say it that way, right that it was their problem and not just hers. In fact, he was probably at fault—after years of sleeping with his infertile wife, he might’ve been careless. Be

sides, he’d been drinking every time he met up with Ester. Remembering whether he could’ve made a mistake was as impossible as recalling the details of brushing his teeth that morning. It had all been so automatic, rolled along so smoothly, until now.

The grizzled old bartender asked what they wanted, then brought the two cups of mineral water Joachim ordered, probably after spitting in them. One of his eyes didn’t quite follow the other, and Joachim watched it covertly, unsure whether it was real. He felt like the old man was trying to pull one over on him, like life was.

“When?” he asked, because that was the kind of question people asked, and because he had to say something.

It was a stupid question because they’d been sleeping together such a short amount of time, and when she told him, the date meant nothing to him. He couldn’t even begin to think about the possibility of having a baby with the scared, half-unknown girl across from him; all he could think about was Helena getting back to the apartment—hopefully she’d stopped for groceries or some other errand—and wondering where he was. A feverish sweat soaked his skin, and his head ached as he forced himself to focus.

“What are you—I mean, what are we going to do?” he asked.

“That’s what I came to ask you.”

Focus, focus, he urged himself. There’s a solution to every problem, an answer to every question. Once in Gymnasium, he’d come down with a stomach virus in the middle of a history exam and bravely sat out all three hours of it before handing in the papers and vomiting at his teacher’s feet. He’d known how furious his parents would be if he didn’t finish it. Vividly, he recalled the dizzy nausea pressing against him like a stiff headwind, and the answers squirming on the pages, mingling with the questions, interchangeable. Everything equally true; everything equally false. He had to relearn to read, to understand German, with every line; had to create the lecture hall around him over and over again through sheer strength of will, like a dreamer trying not to wake up. If he succumbed to the black pounding in his brain, it would all disappear.

But he had not, and he would not now succumb to it. There was a question, and there were possible answers to it. Either she’d keep the baby, or she wouldn’t. If she didn’t plan to, there was little he could do. Accompany her to a clinic, maybe. Talk her through it. Pay. But if that were all she wanted, she would’ve asked him right away. And she would’ve said it differently. “I’m pregnant” was a condition, a potentially transitory state. “We’re having a baby” was a binding plan.

“So you want to keep it?”

She didn’t nod, didn’t shake her head or speak, but in the way she looked at him he knew that she did. There was a softness to the look on her round, childish face, a touching vulnerability. And yet they’d never said I love you or talked about a future together. He couldn’t remember her last name, or whether he’d ever known it. Still, there was no denying his part in this baby. So there was another question, and now he had to focus on choosing from another set of answers.

“You know I’m married,” he said, and with an extreme, almost painful effort, added, “but…” He didn’t know where to go from there. Instead of dealing with the situation at hand, his brain wrestled with the question of whether he could conceal this from Helena, and by what means. Could he justify keeping this secret? The pregnancy might’ve come about during a temporary separation, but he and Helena were back together now. What would he tell her when he came in?

“I know,” she said. “But.”

Neither of them seemed able to say anything else. Perhaps she wanted to but couldn’t, and he wanted nothing more than to leave as soon as possible, to collapse in Helena’s arms and awake as if from a nightmare. But it was no use being melodramatic.

“Well, about the baby, if you need anything…” Yes, that was it; of course she’d need something. Babies were complicated. And expensive. “I’ll certainly help you out… financially.” The last word came into his mouth with a sour foretaste of sickness.

She paled still further, which he wouldn’t have thought possible. He was as ashamed as if he’d hit her, and wanted more than ever to flee.

She swallowed loudly. “Are you going to tell your wife?”

HELENA

Helena arrives at the café a quarter of an hour early and takes a table in the nearly empty interior, with a slight cross-breeze from the open door. There are still a couple of tables left on the sidewalk, but she prefers to retreat to the dim, stifling atmosphere of summer indoors, to hide somewhere she’ll have to be found. This is the advantage of arriving early. She doesn’t have to approach the other tables, asking all the solitary men if they’re Tobias; she doesn’t have to make questioning, hopeful, pathetic eye contact with every passing male. She’s early enough to reasonably assume that she’s the first one here. All she has to do is read her book and try to get her pulse down to a normal level.

She should’ve asked Doro for a picture. She didn’t want to, didn’t even want to send her own with its too broad smile, looking like an applicant who’s been out of work a long time. But it might’ve helped to know what he looks like.

Only two other tables inside the café are occupied: one by a mother and her extensive collection of children, sharing rapidly melting sundaes and speaking a language Helena can’t identify, and one next to the newspaper rack by a generic male form behind a spread paper. That would really have been the thing to do. Why bother with her tiny little novel when she could hide her entire body behind a sprawling issue of Die Zeit? Already, she wishes she hadn’t come. She knows just how he’ll be, and how she will. He’ll say things that got a laugh from other women, and she’ll pretend to find him charming. She’ll keep nodding and smiling through three dates or so, then snap at him under the pressure. He won’t like the real her, whatever that’s supposed to mean. Nor will she like him. But they’ll sit across from each other a few times, each hoping against hope for a ticket out of solitude. Each willing to forgive, to overlook flaws, to swallow the medicine with the sugar, and try to believe that a life with this person wouldn’t be too unbearable.

The man abruptly lowers his paper, and their eyes meet. She looks down at her book. She wasn’t staring at him, really, just into the vague expanse of headlines she can’t quite read from here. But he won’t see it that way. He’s what she’d call pleasant-looking rather than actually handsome—slightly too broad in the jaw with a short beard, overgrown blond hair, and thick eyebrows that would give him a leonine appearance if not for the deep laugh lines in his face and his bashful, puzzled expression. As it is, he better resembles a sheepdog.

In spite of herself, she smiles. It doesn’t matter; Tobias will arrive in a few minutes, and the bearded man will see his mistake and retreat behind his paper again. She looks just to the left of the newspaper man, out the door. She wasn’t watching him; she just happened to pass over him as she turned to look for someone else. For added emphasis, she checks her phone.

One of the first things she did after she and Joachim broke up—after I left, she reminds herself—was to buy a new SIM card. It was the only way she could keep herself under control. Not that she would’ve called him. When she makes a decision, she sticks to it. But there was no other way to stop herself from constantly checking to see whether he’d called, from incessantly, permanently, and pathologically waiting for something she didn’t even really want.

Hearing the crinkle of newsprint, she looks up to see the bearded man standing over her, his paper folded under one arm.

“Tobi,” he says, offering her his hand. “In case you happen to be Helena.”

She nods, briefly at a loss for words.

“Should we get a table outside?”

When they sit down again in the sunlight, they’re two new people: she’s no longer the wary stranger eyeing him through his newspaper, and there’s no longer anything ironic about his smile. For the first time in years, conversation is so easy she doesn’t have to think about it. When her phone rings with the bail cal

l she set up—Doro pretending to be locked out so Helena can rush to her rescue—she doesn’t even pick up. They get through the basics in a few minutes, maybe because this is a set-up and they already know a rough outline of each other: he’s an architect from Bavaria and she’s a graphic designer from the Rhineland. He has two brothers and she’s an only child; neither of them smokes. And then they talk about anything and everything, and she’s astonished that three hours could pass so quickly.

He doesn’t seem to have expected the afternoon to go so quickly, either. He apologizes for having to rush to a fitting—his cousin is having a big wedding and he’s the witness—but they exchange numbers and he says, “I want to see you again. Very, very soon,” before getting their check. When he kisses her on both cheeks, her heart shudders with fear and happiness. She stands a moment watching as he heads toward the S-Bahn station to catch his train, then starts toward Warschauer Strasse for a tram.

But when she reaches the stop in the middle of the road, the airy, pulsing feeling within her won’t allow her to stand still, so she decides to walk home. It’s a long way but she can always catch a train later, once she can think clearly again. A few slugabed songbirds are chirping and the traffic sounds distant, as if she were floating above it. She’s distinctly aware of the red glimmer across from her as she crosses Warschauer Strasse again, but the light seems insignificant, part of a world she’s left behind. She hears the blare of horns honking but something hits her before she has time to turn and look. Her only sensation is shock. She’s out before the pain comes, a butterfly after the windshield, falling lightly to the ground.

Retrograde

Retrograde